For the Water, For Future Generations

Grassroots Indigenous Water Defence fighting pipelines (and more) in Treaty 3 Territory

Peak Magazine, Volume 54, Issue 2

March 2015

Asubpeeschoseewagong—[Early this Spring], activist Clayton Thomas-Muller spoke to a small crowd at the Ne’chee Friendship Centre in Kenora, Ontario. The event, hosted by Grassroots Indigenous Water Defence, and opened by the Grassy Narrows Women’s Drum Group, was billed as a Public Forum on the Energy East Tarsands Pipeline. The event was not intended to be an information session on the technicalities of the pipeline nor on the various Energy Board processes that many environmentalists are focusing on. This meeting of mostly Anishinabe women was more focused on solidarity between frontline Indigenous communities across Turtle Island and on a spiritual imperative to protect the water for future generations.

Thomas-Muller’s current job title is as Extreme Energy Campaigner for 350.org, and his resume includes working with Idle No More, Defenders of the Land, the Indigenous Tarsands Campaign, and the Indigenous Environmental Network. His recent trip to Treaty 3 Territory comes on the heels of an anti-pipeline convergence in Halifax that was also focused on solidarity between frontline Indigenous communities. On the keynote panel moderated by Thomas-Muller, held on Mi’kmaqi Territory was Judy DaSilva from Asubpeeschoseewagong (Grassy Narrows) in Treaty 3, a member of both the Grassy Narrows Women’s Drum Group and Grassroots Indigenous Water Defence.

Thomas-Muller says that, “the role that groups like Grassroots Indigenous Water Defence play for our communities is providing a front line of defence for our land, water, human health and collective rights. They are an expression of community self-determination and provide an important role in supporting our elected leadership in what can be difficult decisions to resist harmful developments like the Energy East Pipeline proposal. Sometimes our provincial and territorial chiefs advocacy organizations can only take things so far and thats were social movement based infrastructure like this group can also be important.”

Treaty 3 Chiefs were recently in the headlines when Grand Council Treaty 3 announced an all Chiefs declaration that stated (amongst other things),

We reaffirm our inherent rights as the original government of these lands and sacred responsibilities to protect the water, the lands, the air, sacred sites, rivers, streams, animals, birds and medicines in all its forms in all parts of Anishinaabe Aki…

Our health as individuals, communities and a Nation depends upon clean, safe drinking water. The right to clean and safe drinking water is a fundamental human right. Many decisions of the Crown, federal and provincial, have violated our fundamental human right and our natural right to clean and safe drinking water…

We are joined together to declare to our Nation, as the political leadership, we are determined to ensure that no oil or bitumen shall be transported through Anishinaabe Aki without our full, prior and informed consent.

At the recent Energy East forum in Kenora, when asked about the Chiefs’ declaration, Thomas-Muller said that it is up to the grassroots to ensure that political leadership “makes the right decision,” which is to say, community organizers have an opportunity to use grassroots mobilization to ensure that leadership holds firm on their commitment to protect the water and the land, and to let the federal and provincial governments know that grassroots land defenders will protect the land and water regardless, through various forms of grassroots mobilizations and direct action, including ceremony and prayer.

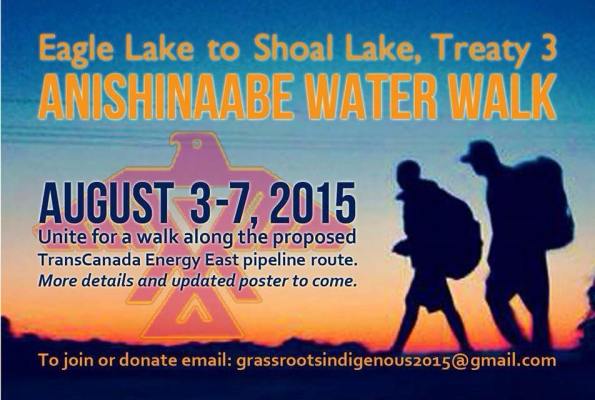

Grassroots Indigenous Water Defence are already deeply engaged in that mobilization effort. On Family Day, February 16, the group held (then) the largest public demonstration in Kenora since the height of Idle No More, as Anishinabe women and youth sang and drummed, and were joined by members of Transitions Initiative Kenora and Winnipeg Indigenous Peoples Solidarity Movement in a picket of one of the downtown’s busiest intersections and a ‘walk’ through the downtown core. On March 16 an even larger action was held by grassroots people of Grassy Narrows against proposed logging in their Territory. On March 22, Grassroots Indigenous Water Defence held a traditional Anishinabe water ceremony and another public demonstration in Kenora for World Water Day.

“World Water Day [was] a day to bring awareness to people in the Kenora area on the threats to this very precious life giving source,” says Judy DaSilva.

Each Day, industry looks to the Kenora area’s abundance of water in terms of production for consumption. Our simple purpose on that day [was] to educate the people about what is threatening this water; there’s mercury poison in the water on the English and Wabigoon Rivers near Grassy Narrows, a [rare earth] mine was approved near Wabaskang, Goliath mine near Wabigoon is looking at mining gold, southern Ontario is always eyeing our area to put their highly toxic nuclear waste in the precambrian rock, Transcanada’s pipeline is going through the process of consultation and approvals to push the oil through these lands. These are the kind of serious water issues people need to look at in Kenora and in Treaty 3 if they want to keep the water pristine for the future generations. We need to be good ancestors.

As DaSilva said, the Water March was about more than just the Energy East Pipeline. Local organizing meetings have also focused on protecting the local waterways, and all water, from a variety of forms of industrial pollution, and discussions have centered on a spiritual imperative to protect the water for youth and for future generations. Part of the brilliance of Grassroots Indigenous Water Defence and other likeminded, similarly organized and inspired groups of mostly Indigenous women, is that by making the focus about a traditional imperative to protect water, they have made space to bring the similar struggles of various isolated and remote communities under a single banner, and given them the momentum of the national anti-petroleum movement. It is necessary to share that spotlight in this way because the threats to land and water are diverse and complexly interconnected.

These interconnections are important. For example, one of the regional issues highlighted at the Water March in Kenora was the Save Big Falls campaign, organized by members of the Namekosepiniik Anishinabe (Trout Lake Anishinabe, mostly members of Lac Seul First Nation). Big Falls is an important site on their traditional canoe route to Trout Lake, which is part of the headwaters of the English River System (the same English River system that flows through Asubpeeschoseewagong Territory). The Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry wants to put a hydro dam at Big Falls against the wishes of the Namekosepiniik Anishinabe and Lac Seul First Nation whose Traditional Territory the Falls are within. The energy from that proposed dam would be used to power (amongst other things) regional pumping stations for the Energy East Pipeline, as well as mining expansion and other development in and around Red Lake, Ontario.

The gold mines in Red Lake (less than 100 kilometers north of the Grassy Narrows reserve) are already the largest and most profitable on the continent and are scheduled for large scale expansion over the next decades. One of the attendant pieces of infrastructure development is a proposed superhighway from Red Lake to Winnipeg—the construction of new transportation corridors being one of the most impactful forms of environmental disruption, with respect to habitat, and as a harbinger of further development. The scale of environmental destruction at Red Lake is somewhat unimaginable. It has been described by the Financial Post as ‘the Fort McMurray of Ontario’.

Red Lake is immediately to the north of Asubpeeschoseewagong Netum Anishinabek (ANA) Territory. The route of the Energy East Pipeline is directly to the south. ANA, more commonly known as Grassy Narrows First Nation is a well-known community when it comes to land and water protection. The Grassy Narrows blockade against clearcut logging in their territory has been in place since 2002 and is known as the longest standing Indigenous blockade in Canada. Grassy Narrows is also one of the two communities primarily affected by one of the largest industrial environmental disasters in Canadian history, the mercury poisoning of the English and Wabigoon River systems, caused by dumping from the Dryden Pulp and Paper Mill in the 1960s and 70s.

While the Red Lake mining boom sits at the headwaters of the English River and the northern end of Asubpeeschoseewagong Territory, to the south, Transcanada’s pipelines and the CN Rail lines carrying both tarsands bitumen and explosive natural gas both cross the Wabigoon River right at its mouth. There is an Energy East pumping station proposed right on Wabigoon Lake—the same lake that the Dryden Pulp and Paper Mill dumped more than ten tonnes of mercury into more than 40 years ago.

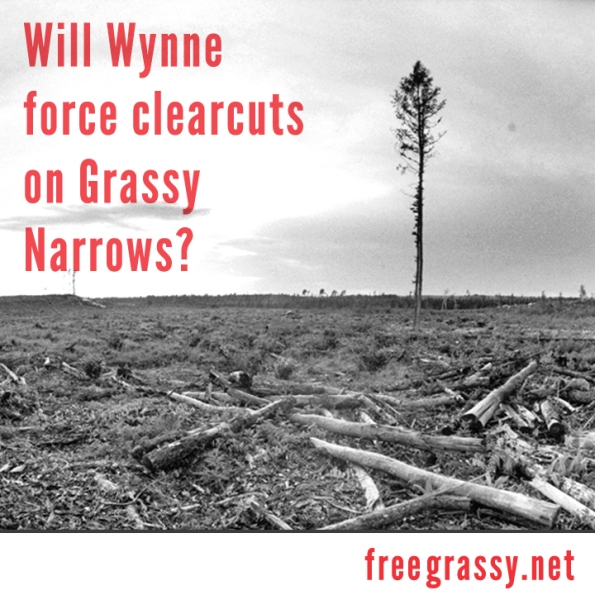

There is also another new mine proposed right on Wabigoon Lake, unapologetically called the Treasury Metals’ Goliath Gold Mine. Both the gold mine and the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry’s (MNRF) long term Forestry Management Plan for the so-called ‘Whiskey Jack’ Forest—which entails widespread clearcutting of Asubpeeschoseewagong Territory, and could see cutting start as early as April 2015—if implemented, would drastically increase the mercury levels in the still poisoned river system which is only in the very early stages of natural recovery. Both new mines and new clearcuts would also do much other damage to the land and water than just raising mercury levels, too: habitat and ecosystem disruption, waste water leaching and dumping, air pollution, soil depletion, contributions to climate change, etc.

The type of threats posed to the waters of Asubpeeschoseewagong, however, are not unique. The nature of industrial development and resource extraction all across Turtle Island is such that there are literally hundreds of First Nations and Indigenous Peoples whose territories are laden with and/or circumscribed by environmental devastation and impacts on human health wrought by economic development projects—mining, oil and gas, forestry, industrial scale agriculture, infrastructure projects, etc. And while these projects happen on the doorsteps of Indigenous Peoples, on their Nations’ Territories, all of these projects contribute to the broader scope of environmental devastation that inevitably impacts all Peoples, through climate change, the destruction of ecosystems and biodiversity, and the poisoning of the air, land and water.

So one of the reasons why Thomas-Muller (and others) has shifted so much of his efforts to this campaign, is that it isn’t just any one community’s water that is threatened—it is everybody’s, since the pipeline crosses hundreds of river basins and waterways on its route, and further, tarsands development remains one of the single most devastating contributors to climate change on the planet; fighting pipelines and oil-by-rail remains one of the most effective ways to challenge tarsands expansion, especially at a grassroots level. However, Thomas-Muller never fails to stress the importance of solidarity with the People of Fort Chipewyan, the primary downstream community most directly impacted by the tarsands; this solidarity is also stressed by the women of Grassroots Indigenous Water Defence.

One of the things that is so impressive about Grassroots Indigenous Water Defence’s organizing efforts against the pipeline, which is another part of why Thomas-Muller was here, is that they are lead by Anishinabe women from communities that have first-hand experience with both the impacts of, and organizing against the impacts of tainted and destroyed water supplies, who understand the importance of organizing for the water, for future generations—women from, amongst other places, Lac Seul, Shoal Lake, and Grassy Narrows.

On the Land: Grassy Narrows Traplines – Interviews with members of the Swain family

With the Grassy Narrows “Trappers’ Case” finally reaching the Supreme Court this week, it seemed like a good time to repost a write up of the interviews I did with Chrissy Swain, her son Edmond Jack, and grandfather Jim Swain, wherein we talked about the recent re-acquisition of a family trapline and the importance of trapping and being on the land for the history and future of Asubpeeschoseewagong Netum Anishinabek, the People of Grassy Narrows.

This interview originally appeared as an article in Peak Magazine‘s recent issue on “Intergenerational Movements.”

***

On the Land: A Grassy Narrows Family talks about the History and Future of their Relationship with Trapline and the Lands of Asubpeeschoseewagong Netum Anishnabek Territory

For me doing this isn’t just about protecting the land, it’s about reviving our people, bringing that spirit back to our people. And that’s what’s going to bring the spirit back to our people, is to keep this land.

-Chrissy Swain

On February 9, 2014, Maryanne Swain finally received word from the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) that she had been approved as the new title holder for trapline KE056, located in Ontario Forestry Management Unit (FMU) #490, also known as the Whiskey Jack Forest.

The Whiskey Jack Forest roughly overlaps with the Traditional Territory of Asubpeeschooseewagaon Netum Anishnabek, also known as Grassy Narrows First Nation, and has been more or less protected from Industrial logging for over a decade by the longest standing blockade in the country.

In April of this year, the MNR’s 10 year Forestry Management Plan (FMP) for the Whiskey Jack Forest comes into effect, which means that for the first time since the blockade went up in 2002, the heart of Grassy Narrows Territory in Northwest Ontario is under immediate threat from industrial scale clearcut logging operations.

A March 1 statement from a new Grassy Narrows Youth Group says, “The new clearcutting plan threatens our home, including lands that our decade long blockade has protected. Our community’s leadership, both grassroots and Band Council, have firmly rejected the new cut plan and contested the Government’s right to make decisions regarding our Territory.”

One of the two Youth organizers quoted in the statement is Edmond Jack, Maryanne Swain’s grandson. His mother, Maryanne’s daughter is Chrissy Swain, a former Grassy Narrows Youth leader and a part of the Grassy Narrows Womens’ Drum Group, who, along with one of her sisters, is often credited with the act of starting the blockade back in the winter of ’02. She is a tireless land defender and advocate for her community.

Jack, in the Youth Group Statement, says, “Not only does the plan threaten my family trapline, but it also threatens the traditional knowledge of future generations who cannot yet speak for themselves.”

Trapline KE056 falls on the south and west shores of Keys Lake, a pristine spring fed lake that was spared from the industrial mercury poisoning of the river system in the ‘60s from which new generations in Grassy Narrows continue to suffer. This past summer, as part of the Annual Grassy Narrows Youth Gathering, a one day blockade of the roadway to Keys Lake was enacted, declaring long term intent on the part of the community’s Youth and grassroots land defenders to protect the lake.

The FMP has six separate cut blocks scheduled for clearcutting within the Swain family trapline, and another six in the adjacent trapline. One of the clearcut blocks will tear out the heart of the Swain’s trapline, spanning from Keys Lake to the neighbouring Tom Lake. Others appear, from the available maps, to engulf at least two of the natural springs that feed Keys Lake.

Ontario’s new 10 year logging plan will clearcut over 500 square kilometers of the Whiskey Jack Forest, with over 50% of Grassy Narrows lands having already been previously logged.

I had the opportunity to sit down with Chrissy Swain, 34, and Edmond Jack, 19, as well as with Maryanne’s father, 78 year old Jim Swain, to ask about the trapline—land which the family has been connected to for as long as they can remember. I consider myself tremendously privileged to have had the opportunity to conduct these interviews, write this article, and work with this family. To all of the Swains and their families, miigwetch.

During these interviews, I asked about the process of (re)claiming the trapline, its history, and the significance of its being brought back into active use by the family.

***

Chrissy Swain: I know that the area that [my mom] asked for, she asked for it because we have family history there. My grandfather was living there as a kid, and I think she had to get affidavits to prove that our family was in that area.

[I just know] stories that my grandpa told, of him being a kid over there. One of the stories he told was about how one time his mom sent him for sugar, and that’s where he had to walk from, from there to the Hudsons Bay [store], and he slept with a relative close by and then the next day walked all the way back to there.

[Keys Lake and that area] is probably just one of the places [his family] stayed. Our people were everywhere.

I’ve heard some stories about that area being a sacred place, that that place was healing because of the spring where the water comes from the earth into that lake, and the medicine that’s all around that lake. And people used to do ceremonies there, and it’s an area where people went fasting. Those are the kinds of things that I heard about that place.

Edmond Jack: I’ve got my trappers certificate, and I think that when the time comes that my grandma won’t be able to use it anymore, then I will the one who takes that trapline in my name.

To me, when my grandma finally got the trapline, it gave me a sense of relief to know that ill have that when I get older.

That whole area where that trapline is, that lake, I remember one of the older people, I think that was Old Tommy Keesick; before I started my Water Walk, he was telling me about Keys Lake becausecause that’s where I was going to be walking for that first day. He told me that that lake has sturgeon, and he was telling me about why that lake was so sacred and precious. He said that the water there is the cleanest water that we have today. None of our other lakes are as clean as that one, because of all the spring water streams that go into it, I think there’s three of them. He told me that when people go there, they’re not supposed to fish there, because of those sturgeons that are in there.

He said the reason that the sturgeon are so sacred is because when it swims at the bottom, people would pray to the sturgeon and honour it like one of our own people. They can’t walk on the land like we can, but they stay under the water near the bottom of the lake, and they’re kind of like the ones who look after the land under there. They’re not much different from us. They know medicines that we could never reach, probably. And he also said that that whole area is, like my mum said, a place for healing and medicines where people would go and find that medicine that they need to clean themselves out. There are all kinds of cedar that grows around there. It’s just a really beautiful place.

I remember my grandpa telling me that people would go over there and fast on an island close by there, where they would go and drop off a young person who was going through their rites of passage. They would sit there for four days… There are lots of things that I’ve heard about Keys Lake. For me it’s just a really sacred area.

The trapline that my grandma got is right on Keys Lake. It’s almost like an asset or something, to be able to use that place… I’d just really like to be able to really take after the lake and keep it as clean as I could.

Jim Swain: I don’t know exactly how it started… how would I go about [explaining] that?

There was a white guy, who we found out later was part of the family. He is a trapper around Silver Lake. And [the trapline on] Keys Lake was up for grabs, and he applied for it. But then, [the MNR] weren’t sure if they would give it to him or not, they’re very strict. So Mary Anne decided that she would find out if it was possible for her to apply.

They wanted its history, of the trapline. But we didn’t know where to start. So, when I went to Kenora to talk to the person, he said, ‘how much do you know about it?’

I said, ‘My grandfather owned it, owned the trapline, and worked it for a while, for years.’

Before that though, [there was an old guy from the community] who had [the trapline on] Scenic Lake already, he owned it. And he asked my grandpa if they could trade traplines, and at the same time he offered some money, not much. That’s how it started… That’s when they signed the agreement. It kept the old man happy. And after that [Scenic Lake] passed on to my Dad and my Unlce, and then I owned it after. I don’t know how many years we trapped there.

So when they asked me the questions, and I said, ‘I was there. I know the area very good.’

I told them that it would be great if one of us could get it back.

I said, ‘how would I go about it?’ He said, write an affidavit. I didn’t know anything about affidavits. But anyway, they explained to me how to write it, even though I made a mistake. The lawyer who looked at it said, ‘you were supposed to do that in front of me, not on your own’. ‘I’ve never done this before,’ I said. But anyway, they accepted it.

And [the ‘white guy’] was also fighting for it, he almost got it. But after about a year they called Maryanne and they were happy with the affidavits, so that’s how she got that trapline.

Other than that, I don’t know what sort of things to tell you, but we did a lot of trapping at Keys Lake when I was young.

We went all around that area, all the way back to Wonderland [Lake]. There used to be Caribou in that area. But after the road came, and other things, they went further north.

It was hard, really, for me [to tell them about Keys Lake specifically], because I’ve been all over the place. I trapped with my Uncle in Wilcox [Lake]. Then I went with my brother in Kilburn [Lake]. By paddle it used to take two weeks to get up there. Then I went with my other uncle to Oak Lake. But the main one was Keys Lake that she wanted me to talk about.

Anyway, the affidavits helped, and she got it. Now it’s up to her and Ed to look after it.

Chrissy Swain: I think and I feel confident that my son is going in the right direction by taking his own initiative and learning to hunt, fish and trap, and learn medicines. And I’m confident that he’s going to use that land in a good way, to teach his kids and raise them on the land, because that’s a big part of our ways that’s been missing. It makes me proud to hear my son say that he wants to protect that place and to keep it as clean as possible for my grandchildren and my great-grandchildren. That’s my hope—that those teachings and that way of life will be carried on.

Edmond Jack: For me, when I do have kids, I could only wait until they get older and hope that they would take in everything that I could teach them, whatever I know by then, to carry on that way of life.

For me, when that time comes, I’m pretty sure that other people will see whatever my kids might be going through, what they’re doing. Other kids will be talking about it; some of them will be talking about partying, some will be talking about playing games, and then hopefully my kids will be talking about what they did all weekend out in the bush, all their little adventures. And to me, that is a good way of putting it out there for future generations. When [future generations] are young, I won’t be able to interact with them as much. But once some of them learn how to do these things, it’s there, in that age group, and it gives me a hope that more young people will take up these things and pick up on lost ways of life.

There are still a lot of things for people to learn.

Our Anishnabe way of life is so shattered; there are just pieces all over the place. Some places have the ceremonies, some places have our traditional ways of hunting, some places have our traditional way of living—they know how to survive in the bush… The more that we try to enforce these things in our community; if we can bring back our ceremonies and our other more down to earth ways of living, I think it would bring a lot of good things into the community.

Jim Swain: I always liked that area. But then, it was good to see different places. It wasn’t long before I got to know what that guy gave us—Scenic [Lake]. I was really young that time.

It seemed like it used to be, for me anyways, it seemed to be a lot of freedom. There was no vehicles, there was nothing or anything going by. Then all of a sudden, when the roads came in, that kind of… I don’t know, it just seemed too civilized.

I guess I thought about travelling on frozen ice, or making portages, having to cut across—we went through all that.

Keys Lake was mostly rocky, that’s how I found it. There was one place there; it looked like there was a cave there. I told another uncle, ‘let’s go down there, take a look.’ He said, ‘no.’ My grandpa said, ‘no, no, no, you gotta be really brave to go down there.’ I said, ‘why?’ He told me why, he said, I don’t know if it really happens, but he said, ‘you go down there and you go past the entrance and it seems like the wall, the cave just closes behind you,’ so I never went down there, I was scared, so I don’t know if it’s true.

Believe it or not, sometimes you hear strange noises at night… But then again, I never believed in seeing something like that, what they talk about so much; big foot and all that. I don’t know if it’s true. But it is true that sometimes you hear strange noises at night…

Of course now it’s getting, like I said, with too many machinery, that you don’t hear them anymore. You used to.

There was one time I was coming out of the house, just at Keys Lake, where the springs open on to the shore there. I heard something, like someone was whistling loud… I stood there for a while and then walked my way to the shore, and it seemed like that’s where that sound came from, from the open water. It was just a beaver coming up to the surface. And then every time his tail would go up and his head would go up and he’d make that high pitched sound—it’s very loud. I don’t really know how to describe it, but it’s like someone is whistling loud.

Me and my cousin there, at Scenic one evening, around midnight, we heard what’s called the Howling Owl. ‘What’s that,’ he said? ‘You never heard that before?’ ‘No,’ he said. And I said it in Ojibway —- it’s a Howling Owl. After we went around that bay, that’s where our log cabin was. It was a good sleep…

These are all the sounds that you hear in the trapline, especially in the spring. And in the fall, I like in the fall, you can hear owls. We used to sit outside around the fire and listen to the predators coming out during their night hunt.

Keys Lake was one of the main routes for trappers that came down from further up—Sidney Lake, Kilburn. They’d stop by the Hudson’s Bay then go try to get to Macintosh where the school was.

I used to have a trapline house that used to be the main stop. They always stopped, sometimes for a couple days, and carry on to wherever they were going. I wrote that down [in the affidavit], how the trappers used to be, that it was a main route, going to Sidney Lake and all over the place.

I think the most interesting part of trapping was moving—you know when the ice starts breaking up, and moving away with the current—sometimes you have to go through that… These were the adventures I remember.

Spring trapping it was good. I used to like it.

That’s another place they had, around Keys Lake. You’d go to Muskeg [Lake]. Muskeg was good for spring trapping.

Other than that, I don’t know what I can say.

But how we got Keys Lake, I don’t know if my affidavit was good, but I know they enjoyed reading it. They accepted it.

I think [in the future], I don’t think it will be as, I don’t know how to say it; There’s too many—it’s gotten too civilized. There’s so much coming in and out of there, at Keys Lake all the way back to Wonderland. And there’s summer cottages over there. I know I really don’t care for it. It’s not like the old days. You didn’t hardly see anyone on your trapline.

In a way I think it is ok. To me, now I think it’s just if you’re looking for adventure or something, it might not be as frontier, if you’d like to call it. You know there’s a house down there and you know there’s somebody else that’s going to be there.

I was 16 or 17. I travelled by myself in mid winter, in mid January, from Anishnabe Lake. There was no roads, nothing. I came down Oak Lake, across that little crossing at Oak Lake Falls. I knew there was a little trappers’ cabin there but I didn’t know if anyone would be there, and I was all by myself, just a young lad. But I made it through there. The people that were there happened to by my uncles and they were happy to see me.

The next morning I was going to go. They said, ‘You’d better not go, it’s cold out there and you’re not dressed right. Yesterday it was warm and you were travelling with the sun, but today it’s not like that. It’ll be nicer tomorrow.’ So I stayed that day and the next morning I went, and came to Grassy. But after that, I got to like where I travelled by myself. The only thing is that I always made sure that I never got caught alone out there in a storm without a cabin. But I was just lucky I guess.

Only one time I did. I was with my brother. We were going to Red Lake. It was February. So we had to find a place to bed for the night in heavy snow. He went and chose, he was lucky to find a rock wall, and he said, ‘that’ll be our shelter for the night.’ He told me to gather up some wood. And he put some logs and sticks to cover it. It wasn’t the warmest place, but it was ok.

I heard of a couple guys who got caught in a storm and still had a couple days before they could get to a cabin. They had no choice, he said. They piled up some snow and covered it up and went in. ‘It didn’t collapse?’ I said. ‘No, we didn’t think about it, I guess’, he said. ‘But it was warm there, cause of the snow we piled up.’

Another thing that I’ve seen them do is that they get boulders and heat them up and put them where they’ll spend the night.

It would be good for the young fellas to learn, I would think anyway. Cause you never can tell: there might be a time where it will be something like the depression, I don’t know, and at least you’ll be ready for it, if you’ve learned to be a trapper. That’s what my grandfather told me. I was going to go back to school. He said, ‘no, wait two years before you go back to school. First learn about trapping. There won’t be that many jobs there all the time.’ I got to enjoy trapping.

It’s the things that you learn, I guess. I didn’t really make my own snowshoes, but I patched them up. I made my own lacings. I learned that. That was something that surprised me. I didn’t know that I could—I used to watch how they laced them. One day I was out around Slant Lake area and my snowshoes broke, I had to get new lacing. So Denis, he’s my uncle but not too close, he had a moose hide, so I fixed it up. No one had shown me, but I’d seen them do it a couple of times, and I did that. Got some water and laid it out in the cold, take all the moose’s fur out and then scrape it. It comes out nice if it’s frozen. I was surprised, it was the first time id tried it. I did ok the first one, but I did it real good on the second. ‘I didn’t know you could mend snowshoes,’ my uncle said. I didn’t know either.

I told my grandpa, ‘I fixed my snowshoes, no one had shown me’. He said, ‘they talk about people having gifts. That’s your gift. No one showed you, you just knew automatically.’

Chrissy Swain: What I see is that it’s always been a fight for our way of life. Because of the things that I’ve seen growing up and the things that I see now, I feel like the only way that we can always remember who we are as Anishanabe people is to have this land and be able to use it. Something that puts that pride inside of is being able to go out on the land and go out on the lakes and fish and hunt and to be out in the forest and be able to connect.

I do see a big change from when I was a kid. There are kids that are aware of what’s going on. People always say that we’ve lost a lot of our ways, but I want t stop saying that we’ve lost that, because I feel it’s always there, and that’s what we’ve got to protect is what’s there, for our kids. They look around and they see people moving and people saying this is not right. When I was a kid I don’t remember seeing that. [But] I do remember feeling it: ‘This is not right. Why do we live this way?’

I remember being eight years old, walking down the road and looking at our houses, saying ‘why do we have to live like this?’ Because I think I was kind of already aware of what living in a town or a city was like, from visiting my mom, or seeing that they had running water, that the grocery store was right there. And I was like, ‘Why is it harder for us? Why does it feel like this?’

For me doing this isn’t just about protecting the land, it’s about reviving our people, bringing that spirit back to our people. And that’s what’s going to bring the spirit back to our people, is to keep this land. That’s the way I look at it and that’s how I feel.

I see that it’s slowly moving, since the Blockade began. There are more young people that are going for their trappers licenses, that are interested in being on the land. You see and hear about a lot of young men that are going out in groups, fishing or hunting together. You hear of and know women that are like, ‘let’s go blueberry picking’, ‘let’s go get cedar.’ So that’s way more than what was in my time.

To me, protecting this land is being successful. Even if it’s just little steps, right now today we can say there’s been a little bit more movement. If we keep going, more is going to come for our kids and for our grandchildren.

Edmond Jack: I think having that trapline kind of gives me a stronger place to stand. I know there’s a proposed clearcut area right in the middle of our trapline, and I know for sure that they’re not going to cut in there. But if they cut in other places it’s still going to have an effect.

To me, stopping the clearcuts is really important because if they do cut all the places that I’ve seen on that map, a lot of damage is going to be done and it’s just going to make sustaining the trapline harder. Animals that we trap and hunt, they have really big territories—some of them are narrow and long, and some of them are wide. And if you cut one area out then that whole thing is going to change. Some of them are going to leave or die. It would pretty much suck the life dry. Our trapline would be depleted. It would almost be pointless to have a trapline if there’s nothing to do out there. Clearcutting companies come in and when they cut down the trees they’re destroying our way of life. I guess having the trapline makes me feel like I have no choice but to fight.

*****

The statement from the Grassy Narrows Youth group concludes with the following:

“Our People have been dealing with the impacts of logging for decades. Our rivers have been poisoned and many traplines have been destroyed. Now, still dealing with mercury poisoning (from the Dryden Paper Mill’s industrial dumping in the 60s), and facing new threats from mining expansion in Asubpeeschoseewagong Territory, the Government is coming back for our trees.

Over the years, Grassy Narrows has been fortunate enough to have support from some Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities and organizations in Ontario and across Turtle Island. This spring, that support will likely be more important than ever and Grassy Narrows organizers expect to call on renewed support from allies. Please be ready to answer our call and to back us up.”

An Update on Logging Plans. A Report from Grassy Narrows, Asubpeeschoseewagong Anishinabek Territory

UPDATED, May 2, 2014

A partial version of this report appeared as an article in theTwo Row Times, April 16 2014.

On April 1 2014, the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources’ (MNR) 10 year Forestry Management Plan (FMP) for the Whiskey Jack Forest came into effect, with over 50 000 hectares – that’s more than 500 square kilometers of forest scheduled for clearcutting.

If you think you have heard of the Whiskey Jack before, it is probably because the Whiskey Jack Forest is one of the names that have been given to an area of land that corresponds with Asubpeeschoseewagong Netum Anishinabek (Grassy Narrows First Nation) Traditional Territory, which has been protected against clearcut logging for over a decade by the longest standing blockade in Canada.

Over 50% of Grassy Narrows Traditional Territory has previously been logged.

The Province does not recognize the land as Grassy Narrows’ Territory. While they tacitly recognize Grassy Narrows Traditional Land Use Area (GNTLUA), that is mostly for the purposes of “assigning” traplines, a right claimed by the MNR. They also call it Forestry Management Unit #490, and the FMP makes it clear that they intend to take the trees, which they view as belonging to the Crown.

Recently the MNR rejected a request from now former Grassy Narrows Chief, Simon Fobister for the management contract (also known as the “Sustainable Forestry License”) for the Whiskey Jack Forest. It took less than 48 hours for the Minister of Natural Resources, David Orazietti to reject the offer, an offer that was also condemned by Kenora MP, now Federal Minister of Natural Resources, Greg Rickford.

The quick rejection and condemnation came after months of silence and refusals to publicly address the issue by the Wynne Government and Orazietti Ministry. Even the NDP’s MNR critic, Dave Vanhouf has refused to comment (though other NDP MPPs have raised the issue in Parliament).

Then on March 28, just days before the plan is to come into effect, a statement was released from the MNR in which Orazietti claimed that this year’s Annual Work Schedule (AWS) will not contain any cutblocks within the GNTLUA, however the AWS is still yet to be released by MNR. They claim to have, for tis year, decided to only log Whiskey Jack cutblocks that do not fall within Grassy Narrows’ Territory, though all of the blocks within the GNTLUA would remain on the 10 year plan.

In a call to the Kenora office of the Ministry of Natural Resources, a representative said that one reason for the delay in releasing the AWS is the request for an Individual Environmental Assessment (IEA) made by the Grassy Narrows First Nation Band Council in January. The Ministry of the Environment has yet to formally reply to the request.

The MNR representative did, however, confirm that they could proceed with an AWS that does not include the areas covered by the IEA immediately, which makes the delay somewhat suspicious.

There is reason for speculation that the MNR will use this delay to attempt to build a wedge between Grassy Narrows and other local First Nations, as well as within the community, in order to pressure Grassy Narrows to drop their IEA request, a tactic that the MNR has used in the past.

Regardless of whether clearcutting is scheduled within the GNTLUA for this year or next, the 10 year plan, as well as the MNR’s own statements (or in some cases, lack thereof) has made the Government’s intent clear.

This reality, and the remaining uncertainties in the ongoing stand against logging, coming from the provincial government, come as even more severe a slight since when she was Minister of Aboriginal Resources, Wynne actually visited Grassy Narrows and promised to help the community find resolution to the ongoing logging conflict and the ongoing problems caused by the mercury poisoning of the English River System, from which new generations of children continue to be affected.

In the 1960’s logging operations dumped an estimated ten metric tonnes of industrial mercury into the waters at the Dryden Paper Mill, resulting in the long term poisoning of the English and Wabigoon River Systems, affecting Grassy Narrows as well as other First Nations.

In an April 2 press release, former Grassy Narrows Chief Simon Fobister said, “the Wynne government is still hanging the threat of a decade of clearcuts over our heads year after year causing great distress for our troubled community. When will Wynne finally promise to respect our voice and commit never to force logging on our community against our will?”

That same day there was an election in Grassy Narrows and a new Chief, Roger Fobister was elected. All indications are that the new Chief Fobister will continue to uphold and support Grassy Narrows’ long stand against logging and for control of their Territory.

In addition to the IEA request, another likely factor in the province’s decision not to log in the GNTLUA this year is the recent commitment by major regional lumber company EACOM to avoid conflict wood from Grassy Narrows. EACOM’s commitment leaves no large operating mills in the region willing to accept conflict softwood from Grassy Narrows Territory after years of boycotts and divestment actions.

Grassy Narrows First Nation Chief and Council (old and new), as well as grassroots organizers in the community have firmly rejected the logging plan, and one reason why the MNR may be slow to commit to a timeline for specific cutblocks within the GNTLUA might be related to the pledges of resistance coming from all corners of the community.

Taina Da Silva, a Youth organizer in the community, and daughter of long-time organizer and grassroots leader Judy Da Silva, said in a recently released statement from the Grassy Narrows Youth Group, “If the logging begins in our territory, I am certain there will already be planned strategies on our part to bring it to a complete halt… It’s important to stop the new logging plan because our traditional way of life depends on the health of the environment.”

Another of the newly formed Youth Group’s core organizers is Edmond Jack, who is also the eldest child of another one Grassy Narrows’ most prominent grassroots voices and former “Youth Leader”, Chrissy Swain. In the March 1 statement, Jack says, “Our organizing is connected through bloodline relations and teachings. Our mothers fought so we could have this land, so we will continue to fight for it… Not only does the plan threaten my family trapline, but it also threatens the traditional knowledge of future generations who cannot yet speak for themselves.”

While the logging plan is the most imminent threat, and one that directly challenges the 12 year old blockade, sadly and shockingly, it is far from being the only dire threat to the long term future of the land and culture in Grassy Narrows Territory.

In the 1950’s, Caribou Falls was dammed for a massive Hydro Project to power logging and mining operations in the region. The damming flooded important parts of the Territories of Grassy Narrows and other local First Nations. This dam was just one of several that have been imposed on the waters of this region over the last 90 years. Currently, the MNR is set to put in yet another major hydro dam.

The new dam planned for Big Falls is in the Traditional Territory of the Namekosipiiw Anishnabe of Lac Seul First Nation, and is a crucial site on their historic migratory canoe route which is still used for trapping (and other cultural and traditional economic) activities.

Big Falls is located at the headwaters of the English River System, the same one still poisoned with mercury.

The new hydro dam at Big Falls is being built, in part, to power the expansion of Gold mining around Red Lake, west of Big Falls and North of Grassy Narrows. Red Lake is already home to the largest and most profitable gold mine in the country, owned by Goldcorp, a Canadian mining giant that has one of the world’s worst records for corporate human rights abuses.

While the Ring of Fire mining projects somewhat stall several hundred kilometers to the east, Red Lake is booming. The Financial Post has called it “the Fort McMurray of Ontario.”

Gold mining is among the most environmentally destructive resource extraction processes on the planet, and poses as grievous and long term a threat to the waters of Grassy Narrows as has been wrought from the mercury poisoning.

The new dam at Big Falls is expected to allow for a massive increase of mining capacity over the next thirty years and also the attendant infrastructural and municipal development in and around Red Lake, which will, over the long term, decimate what may be left of the traplines, even if logging operations are stopped.

And while mining is controlled by the Ministry of Northern Development and Mines (MNDM), not the MNR, it is clear that the Provincial Government under Kathleen Wynne, just like every other government before hers, is firm in their belief that the land is theirs for taking. That idea is unlikely to be an issue in the upcoming provincial election, unfortunately.

One of the other industrial projects that would be powered by a new dam at Big Falls is a new Kenora pumping station for Transcanada’s Energy East Pipeline, which intends to pump Alberta tarsands bitumen westward across the country.

However, campaigns to Save Big Falls and the formation of a new Grassy Narrows Youth Group that “see protecting the land and cultural resurgence as a single inseparable process,” speak from a strong vision of a different future for the forests of this region and for the futures of Anishnabe Peoples who have lived here, in some cases, “since time immemorial.”

The seemingly ongoing fight against the FMP and the longer term struggle to protect the land are at a crucial moment. With the FMP, the Government is seriously challenging the Blockade for the first time in a decade, with the knowledge that they have major development plans for the long term future of this region.

There are also major “rare earth” mining projects scheduled to begin in the west of the territory in the next few years, and more gold mining expansion to the south.

But there are Anishnabe people who are saying no. They are also asking for support.

To conclude the Grassy Narrows Youth Group Statement, Taina Da Silva says the following: “The most important thing supporters can do is to be ready, and commit to both physical and political support should the Province begin logging operations,” she says.

On May 15, the Grassy Narrows “Trappers’ Case” will be argued before the Supreme Court of Canada, though a decision likely won’t come for several months. The case will have major impacts on the interpretation of Treaty Rights within Treaty 3 Territory and beyond.

This is still but a partial assessment of threats to the lands of Grassy Narrows’ Territory. There are other on going concerns including the encroachment of cottage properties onto traplines, granite mines that may be disturbing rock and soil with naturally high uranium levels and impacting drinking waters, increased usage of traplines by non indigenous hunters and recreationalists, and more.

The most concise place to get information and updates on developments at Grassy Narrows, where there is also information on how to support land protection efforts, is at http://freegrassy.net. According to the website, direct political pressure on the Provincial Government is important. The Grassy Narrows Youth Group is also currently fundraising and can be reached at GrassyNarrows.YouthGroup@gmail.com.

Grassy Narrows Youth Gathering, Report back

“Solidarity to Protect Our Waters”

I missed this past weekend’s #NoLogging #NoMercury demonstration for Grassy Narrows in Toronto. The demo saw 7 full marching bands accompanied by busses full of people who descended upon the home of Ontario Premier, Kathleen Wynn. The message being sent was that the people of Ontario demand that the Province adhere to the decision made by the people of Grassy Narrows that there be no more logging on their territory, and that the mercury poisoning of their waters be cleaned up and properly compensated for.

Sunday’s demo comes ten and a half years after a youth led blockade against clear-cut logging was initiated on their territory, and one day after an action by youth and women of Grassy Narrows, accompanied by other Anishnabek youth and women attending the annual Grassy Narrows Youth Gathering, participated in a demonstration of their own, sending a message about their intent to protect the waters of their territory against further damage from mining and other environmental threats.

I missed the demo on Sunday because I was in Grassy Narrows, where I’ve been for a week now, having attended the Youth Gathering and the annual Grassy Narrows Pow Wow in the preceding days. The theme of this year’s gathering was “Solidarity to Protect our Waters.” I had been scheduled to facilitate a workshop on the impacts of mining and Indigenous resistance to mining companies around the world.

I was going to talk about the position of mining in the global economic system of corporate colonial capitalism, and how people from communities who resist Canadian mining companies (the same companies which seek to mine on Indigenous lands here in so called Canada, who are also operating in the global south) are often attacked by paramilitary security forces. I was going to talk about how mining operations rip apart and devastate the earth and the ways they poison the waters in the regions in which they operate. I was also going to talk about the fierce resistance undertaken by Indigenous Peoples around the world and how that resistance is most effective when people are on the land, using it and defending it.

At the workshop I would have talked about how the Federal Conservative’s Navigable Waters Act allows for any lake that is not part of a “navigable waterway” (i.e., a river system) to be re-designated so that it can be used as a “tailing pond” for mining (or other industrial) waste and runoff. I would have talked about how the Ontario Mining Act reserves mining as the priority usage for any land such that any private or crown lands can be staked for mining by any licensed prospector who can prove they have capital to extract the resources: this is a big part of why it is so hard to stop mining companies from carrying out their destructive operations in Ontario, even when they do not have the consent of the Peoples upon whose territories they operate.

I didn’t get the chance to facilitate that discussion, but instead I had the honour of being able to participate, as a settler-ally, in a demonstration on the land, for the water, with some of the fiercest, most inspiring people I know. At the Youth Gathering, I also had the privilege of hearing some of those people—mostly Anishnabek women—talk about the importance of protecting the water, not only for reasons of environmental protection, but as a fundamental part of processes of decolonization and traditional resurgence for Anishnabek Peoples.

The most compelling message, I think, was about the deep connection between the destruction of the waters and the violence against Indigenous women that is endemic to this colonial society. The capitalist raping of the land and patterns of missing and murdered Indigenous women are connected in numerous ways, and combined, amount to a real and primary strategy for destroying Indigenous Nations, cultures and Peoples—genocide—so that the Canadian (and American) Nation State and capitalist corporations can legitimize their theft and plunder of the land: Without the presence of strong Indigenous women in Indigenous communities, Clan-Mother based governance systems of Indigenous Nations cannot function; without access to undestroyed land, Indigenous cultures cannot survive. We talked about deep cultural, political, spiritual and ceremonial connections between Indigenous territories and waters and Indigenous women. We talked about both the destruction of Indigenous lands from resource extraction and the systemic societal devaluing of Indigenous women that makes possible existing and ongoing patterns of missing and murdered Indigenous women, both as forms of explicit active genocidal racism being enacted at the state level with the complicity of all settlers residing here.

At the gathering we also heard about threats to water from fracking and from pipelines, and about the damage done by a Goldcorp gold mine on upstream Lac Seul First Nation Territory at Red Lake and the fight against imminent construction of a new hydro dam at Big Falls. There was also a presentation from one of the founders of Idle No More, and there were ceremonies, traditional teachings and a ‘mini pow wow,’ as well as lots of singing and drumming by the camp fire. For many of the youth, it seemed, teachings from Elders, Clan Mothers and Warriors were highlights of the gathering.

On Sunday, while the demonstration was taking place out front of Premier Wynne’s home in Toronto, I went swimming at some local cliffs in Grassy Narrows Territory with a group 10-12 year old girls who are members of the youngest generation of one of the families here, which I have had the honour and privilege of coming close to over the years, that has been central in the blockade and the ongoing fight here against logging and other forms of environmental destruction. One of the girls looked at the tattoo on my back and asked me what “Resist” means. I told them it means fighting back when people who have more power than us try to hurt the people or places we love and need. She asked me if I meant like when her aunts stopped the logging the trucks here. I told her that was precisely the kind of actions that I was talking about. Another one of the girls pointed out that the word in “Resist” can be rearranged to spell “Sister.”

In a lot of ways, it is those girls and their peers that are the reason that this fight in Grassy Narrows in particular, like other anti-colonial fights led by Indigenous women and youth, is the struggle that I find myself most committed to. It is the understanding of how deep the connection is between the destruction of the land and violence against Indigenous women, as well as knowing how urgent is the need and real the possibility of defeating the destruction of the land and People here on this territory, that keeps me going back to the front lines and back on to the land to resist.

For Prisoners Justice Day I am finally posting my Sentencing Statement from June 26, 2012

I want to write about the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women campaign in Toronto. I want to write about how three different young Indigenous women have been apparently killed this summer in this city, and how like across the country such deaths are so often not taken seriously by the state. I want to write about the connection between these deaths and the murder of a Syrian teenager by Toronto police. I definitely want to recall their names: Cheyenne Fox, Terra Gardner and Bella Laboucan-McLean; Sammy Yatim. I want to write about the connection between the horrific phenomenon of missing and murdered Indigenous women in this country and the capitalist ethos of environmental destruction and how at a really deep level these patterns can be seen as part of one and the same.

But I still haven’t figured out how to write about that.

But it is almost Prisoners’ Justice Day and I figured that I should post something to this blog. After all, the problem of prisons in this system is also connected to the patterns and problems above.

So, below is something that I’d meant to have posted quite a while ago. It is the sentencing statement that I delivered to the court on June 26, 2012 before I went in to jail to serve time for my role in organizing the protests that took over the streets of Toronto during the G20 Summit in the summer of 2010.

Those protests were about a lot more than the G20 and the austerity agenda that was ushered in through those meetings. They were also about all that which I mentioned above, and about people uniting to resist intersecting and overlapping forms of oppression and violence.

Prisoners’ Justice Day is on August 10, this year and every year. While the statement below was my attempt to challenge the Crown and the Court’s processes of persecution that they exacted through the G20 Main Conspiracy Case like they do with all their prosecutions, I hope that people will take the 10th to think about, not only the people in prisons and the history of prisons, prison organizing and resistance, but also the way prisoners’ justice and resistance against prisons intersects with the fight for justice for missing and murdered Indigenous women, for the victims of police murder, and for all families and communities struggling against the ongoing racist legacies of colonialism and capitalism that continue to attack us everyday.

*************

ONTARIO COURT OF JUSTICE

HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN

against

ALEX HUNDERT

************

SENTENCING

BEFORE THE HONOURABLE MR. JUSTICE L. BUDZINSKI

AT TORONTO, ONTARIO, ON JUNE 26, 2012

**********

APPEARANCES:

J. Miller, Esq. Counsel for the Crown

J. Norris, Esq. Counsel for the accused

*************

THE ACCUSED: The first thing I want to address is the point that Mr. Norris finished on. It has been stated throughout these proceedings repeatedly by Mr. Miller, and by several J.P.s, and I think even by yourself, that this case isn’t about politics, and I want to suggest that that’s ridiculous. That everybody who has witnessed this case be it the defence lawyers, be it the media, be it non-politicized family members of the co-accused and community, this is so obviously about politics.

And given that we keep hearing this phrase about putting the reputation of the justice system into disrepute, or anything like that, or other variance of that we have heard, I think every single time, either someone behind the Bench, or the Crown Attorney suggests this isn’t political, it puts the justice system in disrepute.

I think the most concrete evidence of that is when we compare the sentences given to people who were caught breaking a couple windows during the G20, versus what has happened to people who were caught in Vancouver [during the Stanley Cup riot].

There was recently a young man who broke a half dozen windows, was involved in fist fights, smashed up a couple cop cars, he got 1 month. They are trying to give Kelly Pflug-Back, a G20 defendant, 18 to 24 for almost the same set of charges. So to suggest that this isn’t political is, I think, ridiculous.

Further, the way that the Crown, as Mr. Norris also eluded to, has demonized otherwise perfectly normal community groups, I mean, AWOL is a group that existed in Kitchener for almost a half dozen years, the way we were described by the Crown in this case, we were never, ever described by any political people in Kitchener, Waterloo, or by the police that way. This was a new invention that was part of politicizing this case. It is not an accurate description of who we were as a group. And, you know, pictures of me hugging the Mayor of Waterloo after one of our actions from years ago I think would attest to that. This is a fabrication of these OPP guys, and this Crown unit, that we are some kind of evil organization.

I also think –another thing that speaks to that is the tremendous focus that was put on hyperbolic rhetoric. Things that I accept that were clearly offensive and societally unacceptable ideas to put forward, some of the quotes that we heard over and over again [during our bail hearings and at the preliminary inquest], but trying to take quotes that were obviously jokes, and frame them as serious political discourse, and then say that is what makes us more guilty, that is a ploy, and it’s a political ploy. I think it is very clearly a political ploy meant to turn people against us, so that people won’t listen to what we actually have to say. And I think that’s really obvious, and I don’t think — I don’t think the media were duped, and I don’t think the public were duped, and I don’t understand why… I understand why the Crown is insisting on it. I don’t understand why the courts are.

And that’s part of it, I think part of the reason it’s all happened is to put up a smoke screen and make it impossible for people to hear about the alternative ideas that we’re actually putting forward, or to have a reasonable discussion about tactics.

It can’t be illegal for us to talk about the possibility of actions, except the very premise of this case when it was still a conspiracy charge, was that merely being at meetings where people were talking about illegal actions may be part of a conspiracy to do those things, and I don’t know how we are supposed to have any kind of political discourse if we are not allowed to talk about ideas anymore.

I also think this case was really political because as we suspected from the beginning, as the disclosure has suggested through looking at the Intelligence Reports, and as through a number of F.O.I.s [Freedom of Information applications] into various issues, including the 2009 Aboriginal JIG [Joint Intelligence Group] Report will confirm a lot of what this case was about really clearly to people who have looked through it all; it was about targeting a growing network of radical activists.

There has been a burgeoning network over the last half dozen years in this country, of Indigenous Sovereigntists and their allies, migrant justice organizers, and anarchists. And we have seen time and time again in the evidence that those networks are explicitly what are being targeted by the Intelligence operations. We have seen it in who was selected for — to get brought into this case, as opposed to who wasn’t. And then when this JIG report came out, when someone dug it up, half of what they are talking about in that report those networks, anarchists, migrant justice organizers, — in the RCMP’s report about policing aboriginal communities. And that is — they talk about it in the case as part of the goals, but I don’t know how much of the disclosure – you don’t have access to all of the disclosure until it comes before the court.

THE COURT: I want you to understand that your plea, your admission of the facts, constitutes all the information that I have to deal with this case.

THE ACCUSED: Right.

THE COURT: It would be inappropriate for me to read newspapers, and look at what you may have said or done outside, or prior issues that you may have raised before, or the history of anyone, I am isolated by the information I have in this courtroom and nothing more, do you understand that?

THE ACCUSED: I understand that, and I think that’s part of what is – it’s somewhat problematic about the system. I think that this whole process that we have been dragged through is really — has been all about the criminalization of dissent, and I think that if you want to take the position that you can only — that you are very bound by a certain set of parameters, then I would suggest the court is being used as a weapon by the Crown and the police to criminalize dissent. I would suggest, perhaps, the Court has been used in that way.

Dissent has very much been criminalized. It is very clear to most people that things like [the Crown] appealing our bail, given that we weren’t actually accused of anything violent, things like asking for two year sentences for what are essentially thought crimes, that these are about nothing more than intimidating the public to try to scare people from doing the types of things we were doing—like Mr. Miller just said, deterrence. But this is deterrence from thinking. This is deterrence from engaging in politic activity. This is deterrence from community organizing.

Deterrence from smashing windows is catching people smashing windows, and charging them appropriately, not giving them politically motivated sentences for doing so.

And I think it has specifically been about, not just criminalizing the idea that we are not allowed to talk about these things, but in the course of the way their case was put together, actual tactics and methods of political organizing have also been criminalized. The suggestion that merely being at a meeting where something illegal was talked about makes you part of a conspiracy, makes even the most peaceful soft forms of civil disobedience, conspiracies, because how can you plan them without talking about them.

And I think part of the reason why the Crown didn’t want us to go to trial was so that we couldn’t talk about those issues in court, so you couldn’t see all the disclosure, so that there wouldn’t be an actual public conversation on these things.

We were quite explicitly silenced. When I first got out of jail, the –

THE COURT: You are not suggesting your counsel in some way is part of the conspiracy, are you?

THE ACCUSED: No, I am not –I don’t believe in conspiracy.

THE COURT: You did have counsel, and counsel represented you.

THE ACCUSED: Counsel represented me, stuck by in the parameters of a system, and I will — and I am going to get to that a bit, but I think that the fact that we were very explicitly silenced, that I came out of jail and was told, “You’re not allowed to talk· to the media,”

THE COURT: Are you being silenced now?

THE ACCUSED: No. I had to fight. I had to refuse my bail conditions at one point, and then we –

THE COURT: Are you being silenced right now?

THE ACCUSED: Right now, no. But I think this process — there has been a tremendous amount of –

THE COURT: Let’s keep focused on what we are doing right now, that’s all –

THE ACCUSED: But right now is the culmination of four years. It’s not just the culmination of the trial, and since the arrest, it’s also the whole operation. And I think the court has to own some of what the police did. I think the court is much more responsible for what the police did than anyone else in the room, other than the police.

So you know, these lawsuits that are starting to come up, I think the court is somewhat complicit in those things that happened for not having stopped it.

I also think that the process was –was used tremendously to bully us into a deal. We were told –

THE COURT: What do you mean “a deal?”

THE ACCUSED: The plea deal. I totally accept –

THE COURT: Do you want to take a moment to speak to your counsel?

THE ACCUSED: No, I have talked to him about this. I totally accept that I definitely… I’m quite sure I did something illegal in this process. i’m quite sure that the nine months i’m about to serve is relatively appropriate for what I did. I think it’s unfortunate that none of us can tell anyone which parts of what we did are actually illegal.

The Crown approached… once the discussion for a deal was on the table, we were told “it’s all or nothing. Either there’s a group deal, or nobody is getting cut.” This is in a system where one of our co-accused was facing potential deportation if found convicted, where there were 19 year olds only peripherally involved –

THE COURT: Each of the parties were represented by counsel.

THE ACCUSED: Yeah.

THE COURT: The parties had a right to say no, and each of the parties had a right to go to trial. I clearly articulated to you that you do have a right to go to trial—

THE ACCUSED: Yeah.

THE COURT: –and that by entering a plea you are waiving that Constitutional right to have a trial –

THE ACCUSED: I have a right to a trial, but what the system doesn’t—

THE COURT: But hold on, let me –

THE ACCUSED: –afford me –

THE COURT: Let me finish. Let me finish, okay? You have all the freedom in the world to write about whatever you want to write about, or speak about whatever you want to speak about after today. You also have some rights to speak about relevant issues today in the case. But if you are saying in some way that you were coerced, or that you entered a plea against your will, that is a different matter.

THE ACCUSED: I’m not saying it was “against my will,” and I’m not sure quite what “coerced” means, because this whole process, the whole system is inherently coercive. If I don’t pay my taxes, I get in trouble. If I… we live in a coercive society. That is the nature of the authority in our society

THE COURT: And destruction of property is also coercive –

THE ACCUSED: Sure, that’s not what we are talking about.

THE COURT: Well, we are. That is exactly what we are talking about. We are talking—

THE ACCUSED: Okay, well I’ll get –

THE COURT: –about the freedom of speech that has been reduced to coercive acts of violence against property. That is –

THE ACCUSED: I think that —

THE COURT: That is no different than the coercion that you speak about.

THE ACCUSED: I think it is quite different. But to suggest that what we did was somehow more coercive than the way the police and the Crown have used the system that they possess against us —

THE COURT: In a free and democratic society, it is important that both the authorities and the public recognize that it is, I suppose, an issue of faith, and that people treat each other with dignity. Breaches of dignity or self-respect are wrong for either side to employ in any situation. One cannot—

THE ACCUSED: Okay, then

THE COURT: — justify their own use of breach of dignity or respect to other people by saying that the other person disrespected me first. There are revolutions throughout this world. There are panics in different parts of this country, not this country, but other countries right now, where one religious group fights another religious group I or and one particular political group fights another political group only because they are saying, “You did this to me, and I didn’t do this to you, so I’m going to do it back to you.” Unless we return to the fundamental issues of a democratic society, where everyone treats everyone with dignity, recognizing that there is mutual obligations both on the State and the individual, democratic societies will fail.

THE ACCUSED: Well, frankly, I would suggest that the direction this country is going in, and the very austerity agenda we were protesting, is the most violent thing that anyone did out of all of this, and to suggest that we have a wonderful democratic country that we need to protect with the rule of law, given what the austerity agenda they were putting into place that weekend, given what the police did, given what we can see happening in Montreal right now, I think it’s ridiculous. We have got a situation just across the Provincial border that is nearing the type of revolution you are talking about.

THE COURT: You are an intelligent man. I don’t want to engage in a lot of non-topic or non-relevant issues to what is happening here today. Like I say, you are free to pick up a pen, you are free to write, you are free to speak after today, after the sentence is imposed, in any way you wish.

THE ACCUSED: But I am not free to talk about the process right now?

THE COURT: Well, you have to keep it relevant. You have to keep –

THE ACCUSED: I’ve got –

THE COURT: We have got to keep it to how that sentence is relevant to you.

THE ACCUSED: I think that talking about the fact that we were, I would agree probably within the confines of the law, bullied into a deal. I accept I did something wrong, I accept the terms —

THE COURT: I am going to take five minutes. You may want to speak to your lawyer because —

THE ACCUSED: I have talked to my lawyer.

THE COURT: No, no, no. I I want you to-take five minutes because to say that you are bullied into a dealt I think you need to —

THE ACCUSED: I am qualifying the term “bullied” but —

THE COURT: No, no, we are not playing linguistics here.

THE ACCUSED: We have been playing linguistics since the beginning.

THE COURT: No, I am going to —

THE ACCUSED: When he –when Mr. Miller dragged out the dictionary—

THE COURT: No, no

THE ACCUSED: –we started playing linguistics.

THE COURT: I am going to give you five minutes to speak to your lawyer, okay? You can have five minutes –

THE ACCUSED: Well, how about this, why don’t I fire my lawyer right now and you can talk to me. I don’t want the five minutes.

THE COURT: Just keep it to the point then.

THE ACCUSED: I am trying to keep it to the point. Talking about the process and the way this deal happened, how can that not be relevant to the sentencing hearing that is happening right now?

THE COURT: Mr., Miller, is there an issue here of concern by the Crown?

MR. MILLER: No.

THE COURT: I just —

MR. MILLER: No, I understand Mr. Hundert to be saying –he is explaining his motivation for entering a plea. I don’t take it to be somebody overcame —

THE ACCUSED: And that’s not what l’m trying to say either –

THE COURT: Wait a second. Wait a second. Mr Norris, you agree with the —

MR. NORRIS: Your Honour, I agree with Mr. Miller.

THE COURT: Okay.

MR. NORRIS: I think Mr. Hundert has stated his —

THE COURT: Okay, that’s fine, thank you very much. Go ahead.

THE ACCUSED: So I don’t know where I was in all of this, but I think that that all –all of that, I think you have got a system that you preside over that is flawed. I think it is set up to allow the Crowns to bully defendants into plea deals.

I spent a lot of time in jail, not a lot of time, I spent a very small time in jail, but got to talk to some people who have spent half their lives in jail who talk about pleading over and over again to charges they didn’t’ commit because of the way the system’ operates. Bail is used as a coercive mechanism, and the process is used as a coercive mechanism. The process is used as a coercive mechanism to rack up’ convictions. I’m not saying I didn’t do anything wrong. I’m saying it’s a shame that because we –nobody wanted to go to trial — that nobody knows which things are actually illegal. We didn’t set any precedent in this case, and that’s unfortunate, and that doesn’t fulfill justice.

And all I’m saying is that if the Crown had let the people who obviously weren’t guilty, and should have been cut out of this case get cut, and let the people who wanted to go to trial to have a public discourse about all of this go, that that would have been serving everybody’s definition of justice much better.

And I would just caution the Court and the Crown, and everything else involved, to not let this stuff keep happening. If this system is allegedly about justice, avoiding the conversation is not useful.

I also think — I mean one of the things that has happened through these sentencing hearings… You chastised Peter Hopperton for mentioning the Arab Spring. And then Leah Henderson was maybe not chastised, but, you know, when her lawyer submitted the Time magazine cover of the Occupy “person of the year, protester” story, and I think that in the time that has gone… since then it has become clear that these things are connected.

To suggest that the austerity agenda that we were protesting at the G20, and what is happening in Quebec right now is unconnected would be ridiculous. It is clearly connected to austerity –

THE COURT: No, but just to keep it —

THE ACCUSED: No —

THE COURT: Just to keep it understood is that the comments I made were not against the issues. That is not for me to decide or be involved in. The comments I made were in the effectiveness of the method used. The Arab Spring was very much a social media concern –

THE ACCUSED: That’s not actually true.

THE COURT: Well, okay, I –

THE ACCUSED: That is inaccurate.

THE COURT: We can argue here for hours and —

THE ACCUSED: Yeah, but this is my turn to speak.

THE COURT: No, no. But we can’t argue that point because there is no resolution –

THE ACCUSED: There is. There is. You could actually do the research and go back and look at the footage. People were getting killed live on CNN in Cairo. There was — it was a tremendously violent movement. The spirit of the movement was peaceful, and people were supportive of it so they called it a peaceful movement. That’s part of what our global media does. Is when we support things, we call them peaceful. When we don’t support them, we call them violent. It’s part of the way the whole system works.

For example, it has been suggested that one of the really egregious things we did was to be willing to use violence to achieve political ends. I would suggest that almost everybody is willing to do that. You, yourself, are willing to do that. If I refuse to go to jail at the end of this hearing, what is going to happen? You guys in uniforms are going to physically drag me out of this room. That is a use of violence for political ends, and I only bring that up to suggest that the statement, “Using violence for political ends is always wrong,” is it’s a fallacy. It’s not the world we live in.

And I would also suggest that the tactics that were used on the street during the G20 are part of a global history, and a global reality of resistance, and it was one of the first times in recent memory that a street protest in Toronto actually looked like a protest in the rest of the world, and I think that’s part of why it happened. I think people are waking up in this country, that Canada is not some oasis in some messed up world. Canada is actually part of the problem, a big part. And I think since that G20, we have seen a lot more protests starting to look like that, and I think if the direction this country is heading in doesn’t change immediately, the future is going to be full of a lot more of them. And why the courts wouldn’t take that seriously, and recognize where we are actually at in the world, I don’t think it serves anybody any good.